B-25 Mitchell Bomber – Photos and Videos

| SHARE:FacebookTwitter |

During the Second World War, the high adaptability of the B-25 Mitchell Bomber–named in honor of the pioneer of U.S. military aviation, Brigadier General William Lendrum Mitchell–paid off as it served extensively in missions including both high and low altitude bombing, tree-top level strafing, anti-shipping, supply, photo reconnaissance, and other support.

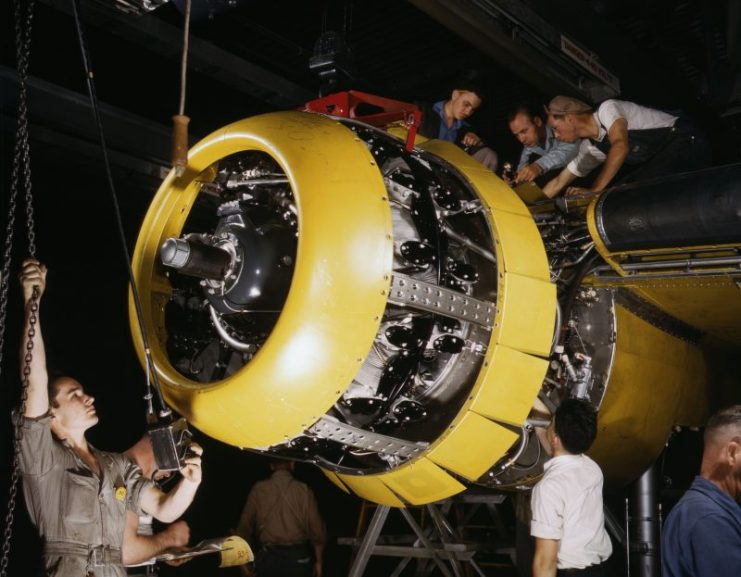

Production of this twin-engine medium bomber commenced in late 1939 by North American Aviation, following a requirement from the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) for a high-altitude medium bomber. By the end of the war, about 9,816 Mitchells were manufactured, with several variants.

Generally, the Mitchell bomber weighed 19,850 pounds when empty, had a maximum take-off weight of 35,000 pounds, and was built to hold a crew of six comprising the pilot and co-pilot, a navigator who doubled as a bombardier, a turret gunner who also served as an engineer, and a radioman who performed duties as a waist and tail gunner.

It was powered by two Wright R-2600 Cyclone 14 radial engines which dissipated about 3,400 hp, and performed with a top speed of 272 mph at 13,000 feet, although it was most effective at a speed of 230 mph.

Its performance range was 1,350 miles with a service ceiling of 24,200 feet.

Anywhere from 12-18 12.7mm machine guns, a T13E1 cannon, and 3,000 pounds of bombs comprised its armament. It had a 1,984-lb ventral shackle and racks, capable of holding a Mark 13 Torpedo and eight 127mm rockets for ground attacks, respectively.

The B-25 performed in all the theaters of the Second World War and was mainly used by the United States Army Air Force, Royal Air Force, Soviet Air Force, and the United States Marine Corps.

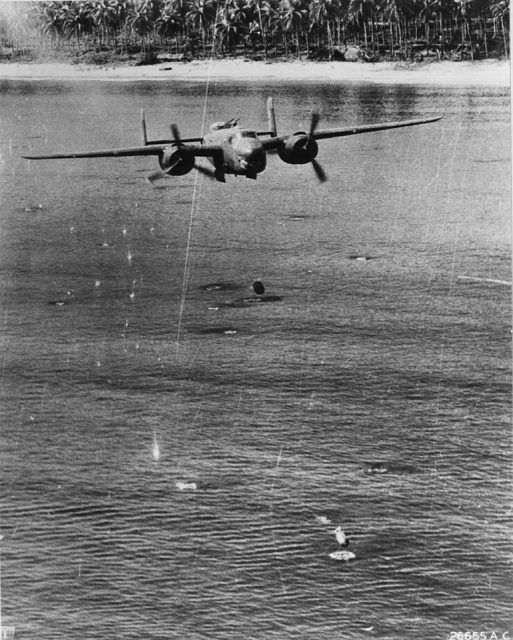

Mitchell bombers participated in campaigns in the Solomon Islands, Aleutian Islands, Papua New Guinea, and New Britain, among others. Owing to the tropical nature of the environment, mid-level bombing was less efficient, and thus the B-25s were adapted to serve as low-altitude attack bombers.

During the Southwest Pacific campaigns, the B-25 enormously contributed to Allied victories as the 5th Air Force devastated the Japanese forces through skip-bombing attacks on ships and Japanese airfields.

In the China-Burma-India theater of the war, B-25s were widely used for interdiction, close air support, and battlefield isolation.

B-25s also took part in campaigns in North Africa and Italy, providing air support for ground forces during the Second Battle of Alamein. They took part in Operation Husky, which was the invasion of Sicily, and accompanied the movement of Allied forces through Italy, where they were instrumental in ground attacks.

The B-25’s extraordinary capabilities as a bomber were first brought to the limelight following their performance in the Tokyo Raid of 18 April 1942, in which the hitherto impregnable home islands of Japan were attacked.

Their sturdiness and ease of maintenance under primitive environmental conditions were characteristics that aided the durability of the B-25s during the war. By the end of the war, they had completed more than 300 missions.

Several B-25s remained in service after World War II, including two that were used by the Biafran side in the Nigerian Civil War, before being retired in 1979.

More photos

Video

Turning Point of WWII – The Battle of Britain – Part 1

| SHARE:FacebookTwitter |

War History Online Presents Part one of the guest Blog from Chris Charland.

The 15th of September 1940 was undoubtedly the decisive turning point in the Battle of Britain, as 56 Luftwaffe aircraft were shot down over the south of England. This one-day tally convinced Adolph Hitler, of Germany, that the Luftwaffe could not gain aerial superiority over the English Channel. Swift control of the waters that separated England from France was vital for the Austrian ‘Little Corporal’s’ proposed invasion of England known as ‘Unternehmen Seelowe’ (Operation Sea Lion) that year.

Unfortunately for him, the British thumbed their noses and threw a monkey wrench into the cogs of the German war machine. Today we celebrate Battle of Britain Sunday with a parade heralding the courage of those who flew off to face seemingly insurmountable odds while dueling with the Luftwaffe, and to honour the memories of those who met their fate in the skies over England, and never returned.

* Canadians played a significant role in the demise of the Luftwaffe, as members of the Royal Air Force, especially No. 242 (Canadian) Squadron, R.A.F. and No. 1 (Fighter) Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force.

Johnny Canuck Joins the RAF

No. 242 Squadron, the R.A.F.’s ‘All Canadian’ unit, which was originally a coastal reconnaissance unit in the First World War, was re-formed on the 30th of October 1939, at R.A.F. Station Church Fenton, Yorkshire. It comprised Canadian aircrew serving in the R.A.F. prior to the Second World War. Initial training commenced in November with a compliment of three Miles Magisters (from No.’s 53 and 66 Squadrons), a single North American Harvard Mk.1 (on loan from No.609 Squadron) and a Fairey Battle Mk.1.(from No.235 Squadron). These numbers were added to by the arrival of seven twin-engine Bristol Blenheim Mk.1F’s and three more single-engine Fairey Battle Mk.1’s in December 1939.

No.242 Squadron received the Hawker Hurricane Mk.1 in March 1940. On the 23rd of March 1940, under command of Squadron Leader Fowler Morgan Gobeil of Ottawa, No.242 (Canadian) Squadron was declared operational for daytime operations. It was cleared to fly night ops the following month on the 11th of May. The unit’s first operational sortie was flown on the 25th of March 1940, when ‘A’ Flight comprising seven Hurricanes flew a convoy patrol.

First Blood

The first Canadian from No.242 Squadron to die in action was Flight Lieutenant John Lewis Sullivan of Smiths Falls, Ontario. On the 14th of May, 1940, he was shot down in Hurricane Mk. I s/n P2621 by a Luftwaffe Hs-123 near Gorroy-le-Chateau, while providing air cover for the evacuation of the beaches at Dunkirk France. Ten pilots of ‘A’ Flight were sent to France on the 16th of May 1940 where they flew with No.’s 607 ‘County of Durham’ and 615 ‘County of Surrey’ fighter squadrons.

By the time the Canadians returned from France, albeit a brief respite from combat, they had accounted for 6 enemy aircraft destroyed. In addition to the death of F/L Sullivan, one squadron member became a Prisoner Of War (Flying Officer Lorne Edward Chambers of Vernon, B.C.) while two others were wounded (Pilot Officer’s Marvin Kitchener Brown of Kincardine, Ontario and Russell Henry Wiens of Jansen, Saskatchewan).

An R.C.A.F. First

No. 242 (Canadian) Squadron reported to RAF Station Biggin Hill, Kent on the 21st of May 1940. The following day, eight of the units Hurricanes shot down a trio of Henschel Hs 126B-1 army co-operation aircraft near Arras, France.

This was a great morale booster, for the squadron up to that point had lost several members in combat without avenging their losses. The honour of the first victory by a member of the R.C.A.F. went to No.242 Squadron’s commanding Officer S/L Gobeil. He shot down a twin-engine Bf 110C ‘Zerstorer’ on the 25th of May.

French Adventures

After numerous patrols, encounters and incidents, No.242 (Canadian) Fighter Squadron in its entirety, was sent back to France. They arrived at Le Mans on the 8th of June, accompanied by the Royal Air Force’s No.17 (F) Squadron. The squadron was in the thick of things. They were on the doorstep of the advancing Germans. The situation was one of desperation. The Germans were literally steam-rolling over the hapless British and French forces. No. 242 (RCAF) Fighter Squadron provided a rear-guard action to allow the British forces time to retreat which would soon lead to the wholesale evacuation from the beaches of Dunkirk. While in France, they moved about from Chateaudun to Ancenis and finally, Nantes.

With little hope of saving France, the Canadians continued to fly on into the face of adversity. It was a lost cause to say the least. On the 18th of June 1939, the last of the pilots flew back to an England which was recovering from the embarrassing shock of the loss of so many personnel and much valuable equipment. The remnants of the squadron were re-assembled at R.A.F. Station Coltishall, Norfolk. It was not until the 9th of July, 1940, that No.242 (RCAF) Fighter Squadron was once again operational.

‘Wooden Legged Wonder’

Two days later, the new commanding officer of No. 242 (Canadian) Squadron and soon to be legendary ‘legless’ pilot, Squadron Leader D.R.S. ‘Douglas’ Bader, shot two Luftwaffe Dornier Do 17Z-2’s. The squadron moved again, this time operating from the airfield at R.A.F. Station Duxford, Cambridgeshire.

Here the Canadian fliers got plenty of opportunity to tangle with the Jerries (Germans) to the north and east of London as part of the Duxford Wing. While operating as part of the Wing, No.242 (Canadian) Squadron scored 11 victories on the 5th of September. The unit would continue with great success during many of its heaviest engagements with the intruding Luftwaffe aircraft.

Changes

The engagements became more sporadic to the point where in October, the squadron unsuccessfully tried its hand at night fighting. By the end of the year, No.242 (Canadian) Squadron lost much of its unique national identity. An influx of Polish and Czech pilots who had managed to escape from their German occupied homelands, as well as British, Australian and Free French, brought the ‘Canadian content’ to about fifty percent. By the middle of the following year, the unit had a pronounced international flavour.

Prelude To War

Canada’s one and only regular fighter squadron No.1 (Fighter) Squadron (based at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia), had been a permanent peacetime unit flying the Northrop Delta Mk.II and Hawker Hurricane Mk.1 prior to being called up for active duty overseas on the 22nd of May, 1940. The decision had been made to send an R.C.A.F. fighter squadron to England along with army co-operation air units in support of the 1st Canadian Division, which was being readied for duty in France.

The move overseas was to take place after the unit was amalgamated with Montreal’s No. 115 (Fighter) Squadron (Auxiliary). No. 115 Squadron, mobilised at the outbreak of war, possessed six aircraft, all of which hardly could be considered fighter material (three North American Harvard Mk.I’s and three Fairey Battles) A number of personnel from units based in Nova Scotia (No.s 8, 10 and 11 Bomber Reconnaissance Squadrons) filled in the remaining slots needed to bring No. 1 up to full squadron compliment.

The squadron left Halifax on the 8th of June,1940 aboard the S.S.Duchess of Athol and the Duchess of Bedford. They arrived at Liverpool England on the 20th, where they proceeded to their new home of R.A.F. Station Middle Wallop, Hampshire. The hostilities in France were over and the Battle of Britain was about to begin. The Hawker Hurricanes that the squadron brought over (using the Watts two-bladed wooden fixed-pitch propellers), were not up to R.A.F. specifications. The aircraft were traded back to the R.A.F. for more modern airframes.

The squadron carried out intensive training as the Battle of Britain was being waged all around them. No. 1 (F) Squadron, R.C.A.F. relocated to Croydon, Surrey on the 4th of July, 1940. During this time, the squadron would remain classified as non-operational. All of that was about to change, as on the 17th of August, 1940, No. 1 (F) Squadron was transferred to the Northolt Sector and declared fully operational. The squadron, led by Squadron Leader Ernie McNabb of Rosthern, Saskatchewan was about to go to war.

By Chris Charland

Senior Associate Air Force Historian

Senior Associate Air Force Historian

Glider Pick-up System

Waco CG-4 Gliders waiting for pickup by C-47 Aircraft

Those that could not be repaired were discarded but because of the cost, $15.580 per glider, an effort was made to retrieve them for future operations.

Leon Spencer writes that to retrieve a Glider, two posts were erected with a nylon loop suspended from it, the Glider was attached to this loop. The tow plane would have a trailing wire with a hook which would catch the loop and the Glider would be airborne and could be towed back to England where it could be inspected and made ready for redeployment.

The architects of the U.S. Army Air Forces glider program determined in the spring 1942 that the large troop and cargo gliders under development were simply too expensive to be abandoned after one combat mission. The fields and pastures in which gliders landed were usually too small and the terrain too uneven for a plane to land and retrieve the gliders. Another means of recovery had to be found. To find an answer to their problem the Air Force turned to Richard C. du Pont, a 1930s national glider soaring champion and the president of our company (All American Aviation) of Wilmington, Delaware. Several years earlier, DuPont's company had developed an aerial retrieval system to pick up U.S. Postal Department mail pouches from the ground by an aircraft on the fly, and had demonstrated to U.S. Air Force officials at Wright Field, Ohio, on 18 July and 22-28 September 1941 that aerial retrieval of gliders was feasible.

This is an Air Show in Cameron, a small rural town in Missouri. The pilots, bike and truck drivers and the photographers are all nuts ! This doesn't border on crazy, it IS crazy! Hold on to your desk, chair, whatever! Best viewed full screen with a HD monitor. This one is waaaay more than just an airshow!!! As GOOD as it gets!!! Click below: https://vimeo.com/100670266

de Havilland Medley

INDOOR RC DEMONSTRATION:

Airbus A310 designed, built and controlled by Martin Müller.

All flaps, spoiler and gear working like the original!

The Best of Canadian Vintage Wings 2008. - YouTube:

'via Blog this'

The last of the fabulous Mk XI Turtle Back Spitfires

Magnificent flying scenes of the last of the fabulous Mk XI Turtle Back Spitfires

Right click on the link and choose "open link in new window"

Duxford Battle of Britain Flightline

FVP Flying

Fly with the Blue Angles

On a particularly hot day, a Royal Australian Air Force English Electric A84 Canberra bomber drops to within 25 feet as thrill-seeking mechanics get ready for the visceral experience of 13,000 lbs of Rolls Royce Avon power full in the face. RAAF Photo

By Dave O'Malley

For the past few years, I have dumped any good shots of low level that I came across on the web into a folder on my hard drive, never knowing what to do with them. Last week, my great friend Ian Coristine sent me an e-mail with a collection of low level photos someone had put together. Many were already in my folder. So, here finally is the contents of my folder, in tribute to my friends Greg “Hard Deck” Williams, whose aggressive attitude once made him engage a pair of A-10s in ACM with his Moonie (and win) and Ian Coristine, who never felt he was flying unless his floats swished in the long grass in a morning sunrise.

Ian Coristine inspects the alfalfa in his Quad City Challenger ultralight.

• Crayfish, crawfish, crawdads

A Douglas A-20G Havoc night fighter of the 417th Night Fighter Squadron does a little daylight low flying down in the weeds possibly near the Orlando, Florida base where they were formed. Their first deployment was to Europe where they immediately re-equipped with Bristol Beaufighters. Today, the unit still trains for a night time job, but flying the F-117 Nighthawk or so-called “Stealth Fighter”.

A P-40 flies down the beach at extreme low level, as Marines practice an amphibious landing somewhere in the Pacific. In order to get this photo, the photographer standing on the beach would have had to have his back to the oncoming P-40 trusting that pilot would do a “buzz job” of the beach and not his hair. Photo via Project 914 Archives, Steve Donacik

A squadron of Luftwaffe Ju-52 Junkers stream low over the Russian countryside near Demjansk, south of Leningrad. In February to May of 1942, the Germans were surrounded by the Red Army. Supplying the Germans during and after the "Demjansk Pocket”, was the role of the air force. Here, low flying in the slow transports was more a survival tactic than a joyride. Photo via Akira Takaguchi

Thought to have been taken in the region of Canterbury, New Zealand in 1944, this shot of an Airspeed Oxford scaring the beejeesus out of half the waiting airmen while the other half remain calm, is a beauty. Photo via Joe Hopwood.

A USAAF P-47 Thunderbolt at extreme low level. Note that the sweep of the camera's pan has bent the buildings in the background

Another shot that has the same effect of bending the buildings in the background (see previous photo). Like our own Spitfire XIV RM873, Griffon-powered PR Spitfire XIX PS890 was sold to the Royal Thai Air Force after the war. She is seen here with 81 Squadron markings and being put through her paces down low at RAF Seletar, Singapore in the summer of 1954 just before her sale. In 1961, PS890 was donated to the Planes Of Fame Museum in California. It was eventually restored and took to the skies again in 2000, albeit with clipped wings and contra-rotating props. It was then purchased by Frenchman Christophe Jacquard and taken to Duxford for the wingtips to be added and a single 5-bladed propeller installed.

While researching images for our P-40 stories over the past year I came across a massive collection of marvelous wartime photos - mostly of P-40s collected by Steve Reno. This P-40 pilot is risking his life only a little less than the man taking the photo of this ridiculously low level pass across the runway. He’s not much higher than he would be if he was standing on his landing gear! If you trace the invisible line of his prop arc, this skilled numbskull’s tips are only about 4 feet off the ground. Photo via Project 914 Archives, Steve Donacik

For many attacking aircraft, safety lay down low in the wave tops beneath enemy radar coverage. Here, a squadron of Douglas A-20 Boston bombers of the RAF's 88 Squadron head to the target over the North Sea. 88 Squadron crews became highly proficient in low-level bombing.

In December 1942, almost 100 aircraft from 2 Group attacked the Philips Valve Factory at Eindhoven including 12 Bostons from 88 Squadron at RAF Swanton Morley. They were led by W/C Pelly-Fry, the CO of 88 Sqn. Pelly-Fry's

aircraft was hit just after he had released his bombs. With much-reduced hydraulic pressure, a large hole in the starboard wing and a coughing and spluttering starboard engine, he narrowly avoided the rooftops but found that the aircraft could not climb above 800 ft, nor could he keep up with the others on the way home. Despite his difficulties, he fought off two FW190s before eventually managing a belly-landing back at Oulton. Deservedly, he was awarded a DSO; the raid also resulted in the award amongst the other crews of another DSO, two DFMs and eight DFCs.

But not all the low-flying was "in the face of the enemy". A former 226 Squdron flight commander, a navigator, related to me one such series of antics by which his crew 'nearly came a cropper'. The pilot and captain of his Boston was Sqn Ldr Shaw Kennedy (who became, after the war, the Air Attache in Prague). Kennedy was a brash Irishman with a wild and wicked sense of humour. His favourite jolly jape was to buzz the German and Italian prisoners of war working the fields around the perimeter of Swanton Morley airfield.

At this point in the story, it helps to understand that Swanton Morley airfield is situated on the top of the only significant hill in central Norfolk. Despite being a mere 150ft or so above sea level, the ground falls away significantly on the north and eastern edges of the airfield into the valley of the River Wensum. Kennedy's "standard approach" was from the east, hugging the bottom of the river valley before banking sharply to port and roaring up the slope at full power over the startled POWs, who immediately hit the dirt to avoid getting a haircut.

Kennedy would then stay low, heading south across the grass airfield, before banking steeply to port again across a small pond, surrounded by trees, to the south of the hangars. He would shave the tops of the trees which, to this day, are shorter in the middle than at the outside, due to his "pruning". This unorthodox procedure worked fine until one, almost fateful, day. As Kennedy rolled out of the left bank to scare the POWs again, his navigator (sitting in the nose) noticed that the POWs had all ducked down well before the Boston would be on them. Sensing that the POWs were up to something, he had no time to tell Kennedy to pull up as all the POWs threw their farming tools in the air as high as they could - straight into the path of the Boston. There were fleeting visions of rakes and spades flashing over the wings and the faint ping of something ricocheting off a prop. Fortunately, Kennedy managed to land the Boston safely. He never buzzed the POWs again! (Story from Squadron Leader Alan. R. James (Ret'd)

Three Japanese Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers with torpedoes aboard, scream extremely low in to the target at Guadalcanal. At this height, the bombers are well set up for a launch of their “fish” and at the same time, as witnessed by the flak explosions above them, somewhat safe from AA fire.

Some aircraft, such as this Spitfire, reach that fine line between crashing and flying low... about 12 inches too low in the case of this 64 Squadron Spitfire with shattered wooden blades. The aircraft, no doubt shaking badly was nursed back to the safety of an Allied base.

An Allied pilot flying a Macchi 200 buzzing Taranto, Italy. It sadly proved that these kind of stunts aren't without danger as the pilot hit a member of the ground crew and more or less decapitated him. The pilot hadn't noticed a thing and after landing was confronted with a dent in his wing's leading edge, containing skull fragments.

I didn't want to include any shots of an aircraft landing or taking off, just low level flight, But this shot of a Lockheed Lodestar dragging its wing in the turn out is interesting enough to include. The aircraft crashed and burned.

A P-47 of the 64th Fighter Squadron, while on a mission to Milan, struck the ground during a low level strafing run. Despite the bent props and crushed chin, the pilot nursed the Jug 150 miles home to Grosseto. Photo via Hebb Russell

Not an extreme low level shot, but this image of a P-40 chasing a B-25 Mitchell over buildings in the Vancouver area is worth a lengthy explanation. Jerry Vernon explains:

"Sgt. Scratch was born in Saskatchewan, July 7, 1919, and enlisted in the RCAF in Edmonton, as R60973 AC2 on July 20, 1940. He earned his wings as a Sergeant Pilot and flew with that rank for a long time. He flew Liberators from Gander, Newfoundland, as a co-pilot on anti-submarine patrols. Scratch was good at his job and was eventually raised to commissioned rank. On two separate occasions, Scratch stole multi-engine bombers and engaged in lengthy low-level and dangerous flying/ Jerry Vernon explains:

“Scratch had injured his leg in a previous Bolingbroke accident, and the powers-that-be felt he did not have enough strength in the leg to control the rudders on a Liberator if he lost an engine. For that reason, both at Gander and at Boundary Bay, they would not give him a captain's qualification, which is what pissed him off.

On the first occasion, they were concerned that he was going to fly the aircraft down to New York City, but he thought better of it, and returned to base. He later told classmates at Boundary Bay that had been his intention. He had taken a Liberator without authority at 0345 hrs on 20 Jul 44, and "for 3 hours and 10 minutes engaged in an exhibition of dangerous low flying over the aerodrome and vicinity." He told the Court of Inquiry that, after 3 years of operational flying on the East Coast, he was determined to participate in another theatre of war.

I suppose that qualified pilots were in such demand that they allowed him to re-enlist as a Sgt. Pilot less than 3 weeks after being dismissed by General Court Martial. Former CPAir PR head Jim McKeachie, a member of the Quarter Century in Aviation Club and 801 Wing, Air Force Assn. of Canada, was on the same course as Don Scratch at Boundary Bay, and had dinner with him in the mess that night before the event here. McKeachie then went off on a leave pass and was not on base the next morning when the Mitchell escapade took place....however, Jim does have his own version of the story, which I have heard from him several times!!

Scratch began a 6-week course at No. 5 OTU as a Mitchell 2nd Pilot and was due to graduate on 11 Dec 44. His Flight Commander regarded him highly and stated in evidence that "He was a very keen, average pilot. He was neat in his appearance and had a pleasant personality. He was very quiet and generally well-liked."

Apparently Scratch wasn't normally a heavy drinker, but got drunk that night before attempting to steal a Liberator and then stealing the Mitchell. Others in his barrackroom stated that they had never seen him drunk...but the Bar Steward testified that he had sold him between 12 and 18 bottles of beer that night!! He attempted to persuade a WD to come with him, but she wisely refused. There is no mention in the file of the Liberator hitting a bridge....the file says it was bogged down in the mud, and a 2/3 full mickey of Jamaica Rum was found dropped down between the pilot seats, with Scratch's fingerprint on it.

The Court of Inquiry notes that he had been drinking beer in the Mess and did not occupy his quarters that night. At 0200, he visited the Stn. Signal Section and offered a drink to the WD on duty.

He did not fly down to Seattle, but the RCAF were afraid that he would, and the P-40s had instructions to shoot him down if he crossed the border, which he did not do. Otherwise, if he stayed inside Canada, they were to stick with him and try to force him to land. He did not fly down Granville St. downtown below the level of the building....as far as I am concerned, it would be physically impossible to do with a Mitchell!! However, per statements from the CO, it sounds like he did fly over parts of the city.

He did fly around and "visit" several of the RCAF stations in the area, possibly Pat Bay and I think Abbotsford for sure....the Court of Inquiry file only mentions Abbotsford and an extensive beat-up of Boundary Bay. In fact, as a kid during WW II, I lived on 176th St., several miles due West of the Abbotsford Airport, and one morning a Mitchell came over our farmhouse at chimney-top level, and I have suspected it may have been Scratch. However, the date seems to rule it out, unless I was back visiting with my grandparents at the time. I moved into Vancouver in the Summer of 1944 and I don't know when my grandfather sold the farm, as he was living over near Cloverdale by the Summer of 1945, as I recall being there when VJ-Day occurred.

I have seen a photo of him buzzing the CO's morning parade at Boundary Bay, well below tower and hangar height. It is in the C of I file in Ottawa, which as I recall also contains some newspaper clippings.

The C of I file says that he beat up Boundary Bay from about 0600 to 0700, then headed for Abbotsford. He then returned and beat up the buildings, runways and parked aircraft at Boundary Bay, incredibly missing some objects by inches. At one point, he flew the entire length of the tarmac between the line of parked aircraft and the hangar, with his props inches off the ground. He could be seen in the cockpit without headphones on, so he could not hear tower transmissions to him.....the CO had gone to the tower at 0630 and taken personal charge of the situation.

The Court of Inquiry decided that, even if he had been drunk when he started out, after several hours of flying and strenuously throwing the aircraft around, he was probably cold sober by the time he crashed.

The C of I ruled that it was not a suicide, as some thought it was. He had flown the aircraft for several hours, up to the point that the fuel should have been exhausted. Mitchell HD343 had taken off at approximately 0454 hrs from the unlit runway and flew around for 5 hrs and 15 minutes until crashing at 1010 hrs, after about 5 hrs and 15 - 20 minutes flying. The Court felt that, as he pulled the aircraft up sharply, one of the engines was starved of fuel and cut out or faltered, thus causing a wingover and the aircraft dove vertically into Tilbury Island, not far from the present Deas Island highway tunnel and the Deas Island Park. I wonder if there is still any trace of the large water-filled crater that is shown in photos??

It had been calculated that the aircraft would run out of fuel about 0930, but it did not crash until 1010 hrs, so that lends some credence to the theory about it running out of fuel.

The Court had considered several possibilities....

Pure accident, ie: loss of control at high speed. No.

Failure of fuel supply to lower engine when wings of aircraft were vertical in last pull-up. With one engine running and the other cutting out, the aircraft would have done a wingover and dived towards the ground. The aircraft was at high speed and flying at 800 - 1000 ft. at the time and the Court felt it would have been impossible to pull out. This was the accepted findings of the Court.

Loss of control due to physical exhaustion....no sleep that night, heavy drinking, 5 hours of violent aerobatic maneouvers, etc. could have resulted in a physical collapse. No.

Suicide. No evidence that he was suicidal, so "No" again.

Insanity. No. He had been examined by RCAF shrinks and the Court had no alternative but to find him sane.

However, the remarks of the CO suggested that Scratch must have been suffering from some sort of mental depression or an inferiority complex. He felt that the flying was so dangerous that no-one in a balanced state of mind would fly that way for such a long period. The CO and several experienced pilots felt that a pilot in a balanced state of mind would have frightened himself so badly that he would have quickly stopped flying this way.

No. 5 OTU operated out of both Boundary Bay and Abbotsford. In general, Mitchells were used at Boundary Bay and Liberators at Abbotsford, and the basic 4 or 5 man crew trained first on the Mitchells and then were joined by the Air Gunners at Abbotsford on Liberators for further work-up.. There wouldn't normally have been many (or any) Liberators at Boundary Bay, but there apparently was at least one there that day. 5 OTU used the Boundary Bay-based Kittyhawks for "Fighter Affiliation Training" for the Liberator Air Gunners, so perhaps that is why one would have been at Boundary Bay.”

'via Blog this'

The last of the fabulous Mk XI Turtle Back Spitfires

Magnificent flying scenes of the last of the fabulous Mk XI Turtle Back Spitfires

Duxford Battle of Britain Airshow

When airshow dates are announced, there are always some that just leap out at you as "must attend" events and a celebration of the Battle of Britain at Duxford has to be one of those. It is true that Duxford's other 2010 shows, the May Air Display and Flying Legends had strong "Battle of Britain" themes, but the September "Battle of Britain Airshow" was the main celebration of the achievements of the RAF in 1940.

As it turned out, the event really was one to remember with perhaps the best flying display held at Duxford for many years and enjoyed record crowds and a superb mix of flying, historic and modern. Here is your chance to view this thrilling air show.

When airshow dates are announced, there are always some that just leap out at you as "must attend" events and a celebration of the Battle of Britain at Duxford has to be one of those. It is true that Duxford's other 2010 shows, the May Air Display and Flying Legends had strong "Battle of Britain" themes, but the September "Battle of Britain Airshow" was the main celebration of the achievements of the RAF in 1940.

As it turned out, the event really was one to remember with perhaps the best flying display held at Duxford for many years and enjoyed record crowds and a superb mix of flying, historic and modern. Here is your chance to view this thrilling air show.

Right click on the link and choose "open link in new window"

Duxford Battle of Britain Flightline

FVP Flying

Fly with the Blue Angles

Lower than a Snake's Belly in a Wagon Rut

On a particularly hot day, a Royal Australian Air Force English Electric A84 Canberra bomber drops to within 25 feet as thrill-seeking mechanics get ready for the visceral experience of 13,000 lbs of Rolls Royce Avon power full in the face. RAAF Photo

By Dave O'Malley

For the past few years, I have dumped any good shots of low level that I came across on the web into a folder on my hard drive, never knowing what to do with them. Last week, my great friend Ian Coristine sent me an e-mail with a collection of low level photos someone had put together. Many were already in my folder. So, here finally is the contents of my folder, in tribute to my friends Greg “Hard Deck” Williams, whose aggressive attitude once made him engage a pair of A-10s in ACM with his Moonie (and win) and Ian Coristine, who never felt he was flying unless his floats swished in the long grass in a morning sunrise.

Ian Coristine inspects the alfalfa in his Quad City Challenger ultralight.

• Crayfish, crawfish, crawdads

They loved to fly low in World War Two

A Douglas A-20G Havoc night fighter of the 417th Night Fighter Squadron does a little daylight low flying down in the weeds possibly near the Orlando, Florida base where they were formed. Their first deployment was to Europe where they immediately re-equipped with Bristol Beaufighters. Today, the unit still trains for a night time job, but flying the F-117 Nighthawk or so-called “Stealth Fighter”.

A P-40 flies down the beach at extreme low level, as Marines practice an amphibious landing somewhere in the Pacific. In order to get this photo, the photographer standing on the beach would have had to have his back to the oncoming P-40 trusting that pilot would do a “buzz job” of the beach and not his hair. Photo via Project 914 Archives, Steve Donacik

A squadron of Luftwaffe Ju-52 Junkers stream low over the Russian countryside near Demjansk, south of Leningrad. In February to May of 1942, the Germans were surrounded by the Red Army. Supplying the Germans during and after the "Demjansk Pocket”, was the role of the air force. Here, low flying in the slow transports was more a survival tactic than a joyride. Photo via Akira Takaguchi

Thought to have been taken in the region of Canterbury, New Zealand in 1944, this shot of an Airspeed Oxford scaring the beejeesus out of half the waiting airmen while the other half remain calm, is a beauty. Photo via Joe Hopwood.

A USAAF P-47 Thunderbolt at extreme low level. Note that the sweep of the camera's pan has bent the buildings in the background

Another shot that has the same effect of bending the buildings in the background (see previous photo). Like our own Spitfire XIV RM873, Griffon-powered PR Spitfire XIX PS890 was sold to the Royal Thai Air Force after the war. She is seen here with 81 Squadron markings and being put through her paces down low at RAF Seletar, Singapore in the summer of 1954 just before her sale. In 1961, PS890 was donated to the Planes Of Fame Museum in California. It was eventually restored and took to the skies again in 2000, albeit with clipped wings and contra-rotating props. It was then purchased by Frenchman Christophe Jacquard and taken to Duxford for the wingtips to be added and a single 5-bladed propeller installed.

While researching images for our P-40 stories over the past year I came across a massive collection of marvelous wartime photos - mostly of P-40s collected by Steve Reno. This P-40 pilot is risking his life only a little less than the man taking the photo of this ridiculously low level pass across the runway. He’s not much higher than he would be if he was standing on his landing gear! If you trace the invisible line of his prop arc, this skilled numbskull’s tips are only about 4 feet off the ground. Photo via Project 914 Archives, Steve Donacik

For many attacking aircraft, safety lay down low in the wave tops beneath enemy radar coverage. Here, a squadron of Douglas A-20 Boston bombers of the RAF's 88 Squadron head to the target over the North Sea. 88 Squadron crews became highly proficient in low-level bombing.

In December 1942, almost 100 aircraft from 2 Group attacked the Philips Valve Factory at Eindhoven including 12 Bostons from 88 Squadron at RAF Swanton Morley. They were led by W/C Pelly-Fry, the CO of 88 Sqn. Pelly-Fry's

aircraft was hit just after he had released his bombs. With much-reduced hydraulic pressure, a large hole in the starboard wing and a coughing and spluttering starboard engine, he narrowly avoided the rooftops but found that the aircraft could not climb above 800 ft, nor could he keep up with the others on the way home. Despite his difficulties, he fought off two FW190s before eventually managing a belly-landing back at Oulton. Deservedly, he was awarded a DSO; the raid also resulted in the award amongst the other crews of another DSO, two DFMs and eight DFCs.

But not all the low-flying was "in the face of the enemy". A former 226 Squdron flight commander, a navigator, related to me one such series of antics by which his crew 'nearly came a cropper'. The pilot and captain of his Boston was Sqn Ldr Shaw Kennedy (who became, after the war, the Air Attache in Prague). Kennedy was a brash Irishman with a wild and wicked sense of humour. His favourite jolly jape was to buzz the German and Italian prisoners of war working the fields around the perimeter of Swanton Morley airfield.

At this point in the story, it helps to understand that Swanton Morley airfield is situated on the top of the only significant hill in central Norfolk. Despite being a mere 150ft or so above sea level, the ground falls away significantly on the north and eastern edges of the airfield into the valley of the River Wensum. Kennedy's "standard approach" was from the east, hugging the bottom of the river valley before banking sharply to port and roaring up the slope at full power over the startled POWs, who immediately hit the dirt to avoid getting a haircut.

Kennedy would then stay low, heading south across the grass airfield, before banking steeply to port again across a small pond, surrounded by trees, to the south of the hangars. He would shave the tops of the trees which, to this day, are shorter in the middle than at the outside, due to his "pruning". This unorthodox procedure worked fine until one, almost fateful, day. As Kennedy rolled out of the left bank to scare the POWs again, his navigator (sitting in the nose) noticed that the POWs had all ducked down well before the Boston would be on them. Sensing that the POWs were up to something, he had no time to tell Kennedy to pull up as all the POWs threw their farming tools in the air as high as they could - straight into the path of the Boston. There were fleeting visions of rakes and spades flashing over the wings and the faint ping of something ricocheting off a prop. Fortunately, Kennedy managed to land the Boston safely. He never buzzed the POWs again! (Story from Squadron Leader Alan. R. James (Ret'd)

Three Japanese Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers with torpedoes aboard, scream extremely low in to the target at Guadalcanal. At this height, the bombers are well set up for a launch of their “fish” and at the same time, as witnessed by the flak explosions above them, somewhat safe from AA fire.

There is often a price to pay.

'One more beat-up, me lads.' Flying Officer Cobber Kain, DFC, a New Zealander and the RAF's first ace of the Second World War makes a fatal mistake. On the 6th of June 1940, Kain was informed he would be returning to England the next day. The following morning, a group of his squadron mates gathered at the airfield at Échemines, France to bid him farewell as he took off in his Hurricane to fly to Le Mans to collect his kit. Unexpectedly, Kain began a "beat-up" of the airfield, performing a series of low level aerobatics in Hurricane I L1826. Commencing a series of "flick" rolls, on his third roll, the ace misjudged his altitude and hit the ground heavily in a level attitude. Kain died when he was pitched out of the cockpit, striking the ground 27 m in front of the exploding Hurricane. Kain is buried in Choloy Military Cemetery.

Some aircraft, such as this Spitfire, reach that fine line between crashing and flying low... about 12 inches too low in the case of this 64 Squadron Spitfire with shattered wooden blades. The aircraft, no doubt shaking badly was nursed back to the safety of an Allied base.

An Allied pilot flying a Macchi 200 buzzing Taranto, Italy. It sadly proved that these kind of stunts aren't without danger as the pilot hit a member of the ground crew and more or less decapitated him. The pilot hadn't noticed a thing and after landing was confronted with a dent in his wing's leading edge, containing skull fragments.

I didn't want to include any shots of an aircraft landing or taking off, just low level flight, But this shot of a Lockheed Lodestar dragging its wing in the turn out is interesting enough to include. The aircraft crashed and burned.

A P-47 of the 64th Fighter Squadron, while on a mission to Milan, struck the ground during a low level strafing run. Despite the bent props and crushed chin, the pilot nursed the Jug 150 miles home to Grosseto. Photo via Hebb Russell

The strange end of Donald Scratch

Not an extreme low level shot, but this image of a P-40 chasing a B-25 Mitchell over buildings in the Vancouver area is worth a lengthy explanation. Jerry Vernon explains:

"Sgt. Scratch was born in Saskatchewan, July 7, 1919, and enlisted in the RCAF in Edmonton, as R60973 AC2 on July 20, 1940. He earned his wings as a Sergeant Pilot and flew with that rank for a long time. He flew Liberators from Gander, Newfoundland, as a co-pilot on anti-submarine patrols. Scratch was good at his job and was eventually raised to commissioned rank. On two separate occasions, Scratch stole multi-engine bombers and engaged in lengthy low-level and dangerous flying/ Jerry Vernon explains:

“Scratch had injured his leg in a previous Bolingbroke accident, and the powers-that-be felt he did not have enough strength in the leg to control the rudders on a Liberator if he lost an engine. For that reason, both at Gander and at Boundary Bay, they would not give him a captain's qualification, which is what pissed him off.

On the first occasion, they were concerned that he was going to fly the aircraft down to New York City, but he thought better of it, and returned to base. He later told classmates at Boundary Bay that had been his intention. He had taken a Liberator without authority at 0345 hrs on 20 Jul 44, and "for 3 hours and 10 minutes engaged in an exhibition of dangerous low flying over the aerodrome and vicinity." He told the Court of Inquiry that, after 3 years of operational flying on the East Coast, he was determined to participate in another theatre of war.

I suppose that qualified pilots were in such demand that they allowed him to re-enlist as a Sgt. Pilot less than 3 weeks after being dismissed by General Court Martial. Former CPAir PR head Jim McKeachie, a member of the Quarter Century in Aviation Club and 801 Wing, Air Force Assn. of Canada, was on the same course as Don Scratch at Boundary Bay, and had dinner with him in the mess that night before the event here. McKeachie then went off on a leave pass and was not on base the next morning when the Mitchell escapade took place....however, Jim does have his own version of the story, which I have heard from him several times!!

Scratch began a 6-week course at No. 5 OTU as a Mitchell 2nd Pilot and was due to graduate on 11 Dec 44. His Flight Commander regarded him highly and stated in evidence that "He was a very keen, average pilot. He was neat in his appearance and had a pleasant personality. He was very quiet and generally well-liked."

Apparently Scratch wasn't normally a heavy drinker, but got drunk that night before attempting to steal a Liberator and then stealing the Mitchell. Others in his barrackroom stated that they had never seen him drunk...but the Bar Steward testified that he had sold him between 12 and 18 bottles of beer that night!! He attempted to persuade a WD to come with him, but she wisely refused. There is no mention in the file of the Liberator hitting a bridge....the file says it was bogged down in the mud, and a 2/3 full mickey of Jamaica Rum was found dropped down between the pilot seats, with Scratch's fingerprint on it.

The Court of Inquiry notes that he had been drinking beer in the Mess and did not occupy his quarters that night. At 0200, he visited the Stn. Signal Section and offered a drink to the WD on duty.

He did not fly down to Seattle, but the RCAF were afraid that he would, and the P-40s had instructions to shoot him down if he crossed the border, which he did not do. Otherwise, if he stayed inside Canada, they were to stick with him and try to force him to land. He did not fly down Granville St. downtown below the level of the building....as far as I am concerned, it would be physically impossible to do with a Mitchell!! However, per statements from the CO, it sounds like he did fly over parts of the city.

He did fly around and "visit" several of the RCAF stations in the area, possibly Pat Bay and I think Abbotsford for sure....the Court of Inquiry file only mentions Abbotsford and an extensive beat-up of Boundary Bay. In fact, as a kid during WW II, I lived on 176th St., several miles due West of the Abbotsford Airport, and one morning a Mitchell came over our farmhouse at chimney-top level, and I have suspected it may have been Scratch. However, the date seems to rule it out, unless I was back visiting with my grandparents at the time. I moved into Vancouver in the Summer of 1944 and I don't know when my grandfather sold the farm, as he was living over near Cloverdale by the Summer of 1945, as I recall being there when VJ-Day occurred.

I have seen a photo of him buzzing the CO's morning parade at Boundary Bay, well below tower and hangar height. It is in the C of I file in Ottawa, which as I recall also contains some newspaper clippings.

The C of I file says that he beat up Boundary Bay from about 0600 to 0700, then headed for Abbotsford. He then returned and beat up the buildings, runways and parked aircraft at Boundary Bay, incredibly missing some objects by inches. At one point, he flew the entire length of the tarmac between the line of parked aircraft and the hangar, with his props inches off the ground. He could be seen in the cockpit without headphones on, so he could not hear tower transmissions to him.....the CO had gone to the tower at 0630 and taken personal charge of the situation.

The Court of Inquiry decided that, even if he had been drunk when he started out, after several hours of flying and strenuously throwing the aircraft around, he was probably cold sober by the time he crashed.

The C of I ruled that it was not a suicide, as some thought it was. He had flown the aircraft for several hours, up to the point that the fuel should have been exhausted. Mitchell HD343 had taken off at approximately 0454 hrs from the unlit runway and flew around for 5 hrs and 15 minutes until crashing at 1010 hrs, after about 5 hrs and 15 - 20 minutes flying. The Court felt that, as he pulled the aircraft up sharply, one of the engines was starved of fuel and cut out or faltered, thus causing a wingover and the aircraft dove vertically into Tilbury Island, not far from the present Deas Island highway tunnel and the Deas Island Park. I wonder if there is still any trace of the large water-filled crater that is shown in photos??

It had been calculated that the aircraft would run out of fuel about 0930, but it did not crash until 1010 hrs, so that lends some credence to the theory about it running out of fuel.

The Court had considered several possibilities....

Pure accident, ie: loss of control at high speed. No.

Failure of fuel supply to lower engine when wings of aircraft were vertical in last pull-up. With one engine running and the other cutting out, the aircraft would have done a wingover and dived towards the ground. The aircraft was at high speed and flying at 800 - 1000 ft. at the time and the Court felt it would have been impossible to pull out. This was the accepted findings of the Court.

Loss of control due to physical exhaustion....no sleep that night, heavy drinking, 5 hours of violent aerobatic maneouvers, etc. could have resulted in a physical collapse. No.

Suicide. No evidence that he was suicidal, so "No" again.

Insanity. No. He had been examined by RCAF shrinks and the Court had no alternative but to find him sane.

However, the remarks of the CO suggested that Scratch must have been suffering from some sort of mental depression or an inferiority complex. He felt that the flying was so dangerous that no-one in a balanced state of mind would fly that way for such a long period. The CO and several experienced pilots felt that a pilot in a balanced state of mind would have frightened himself so badly that he would have quickly stopped flying this way.

No. 5 OTU operated out of both Boundary Bay and Abbotsford. In general, Mitchells were used at Boundary Bay and Liberators at Abbotsford, and the basic 4 or 5 man crew trained first on the Mitchells and then were joined by the Air Gunners at Abbotsford on Liberators for further work-up.. There wouldn't normally have been many (or any) Liberators at Boundary Bay, but there apparently was at least one there that day. 5 OTU used the Boundary Bay-based Kittyhawks for "Fighter Affiliation Training" for the Liberator Air Gunners, so perhaps that is why one would have been at Boundary Bay.”

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)